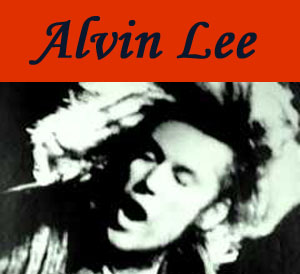

Alvin Lee - Still On The Road to Freedom

Interviews 2012

Alvin's newest CD, Still On the Road to Freedom

has been released on Rainman Records in the

USA and in Europe on Repertoire Records.

Alvin's newest CD, Still On the Road to Freedom

has been released on Rainman Records in the

USA and in Europe on Repertoire Records.

We've printed a few of Alvin's most recent

interviews discussing Still On

the Road to

Freedom ...but please remember

to visit the

websites of the interviewers.

And don't forget

to catch some of the reviews.

Vintage Rock

.jpg)

The Alvin Lee Interview

By Shawn Perry

Discussion about guitar heroes from the 1960s

typically revolves around Jimi Hendrix, Eric

Clapton, Jeff Beck, Jimmy Page, with an occasional

shout-out to Pete Townshend, Duane Allman

and Jerry Garcia. Of course, there were many

other able-bodied guitarists from the era

who could swing with the best of them. One

man who regularly topped the polls and still

commands a hefty penance of reverence is

Alvin Lee.

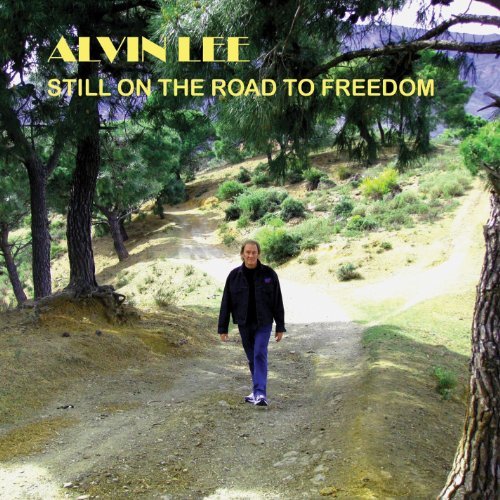

As the guitarist, voice, songwriter and focal

point of Ten Years After, Lee’s furious

playing propped up by a no-nonsense, semi-rockabilly

approach was key to the band’s live

performances. Nowhere is this more apparent

than by the 10-minute scene from the Woodstock

movie featuring Lee and TYA blazing through

“I’m Going Home.” By the

time the band made its way to the mainstream,

Lee had decided to switch gears and make

his first solo album (with Mylon LeFevre)

boosting a title that more or less summed

up his feelings at the time — On The Road To Freedom.

In the years since, Alvin Lee has not become

a superstar solo act, but he’s cranked

out over a dozen albums of varying styles

and disciplines, and worked with people like

George Harrison, Mylon LeFevre, Ron Wood,

Scotty Moore and D.J. Fontana. His 2012 release,

Still On The Road To Freedom, is simply, as he told me during the following

interview, a reassertion of his independence,

making “free music for the soul.”

At 67, living comfortably in Spain, playing

as fluidly and furiously as ever —

Alvin Lee is on a road to freedom most certainly

paved with gold.

Hi Alvin. It’s great to be speaking

with you today. How’s it

going?

I’m doing fine. Thank you very much.

How is it in Spain today?

Oh, it’s warm as usual. Pretty much

like California. Where are you exactly?

I'm in Long Beach, California.

Great. I only ask because I was talking to

a guy yesterday for about 20 minutes, and

he said, “Well, if you’re ever

Detroit‛&” And I said, “Oh,

you’re in Detroit?” And we went

on for another half an hour, talking about

Detroit. That’s a rock ‘n roll

city. Long Beach Arena‛&I remember

it well...

I saw you there in the late 70s with Ten

Years Later.

Oh yeah? Cool.

So, let’s get into Still On The Road To Freedom, the sequel to your 1973 album, On The Road To Freedom.

It’s not really a sequel. It's just

the title track. I wrote the title song,

"Still On The Road To Freedom.”

It's not meant to be a sequel. I think someone

said that in the anecdote. It doesn’t

matter. It’s an extension‛&no,

it’s not even that (laughs). The only

link is the freedom to write music I want.

On The Road To Freedom was about that, and Still On The Road To Freedom is about that too.

You don’t have the same musicians as

the first one. You have bassist

Pete Pritchard,

drummer Richard Newman, and keyboardist

Tim

Hinkley, who played on the first

one.

That’s right. Tim has playing keyboards

with me for years since ’72. In fact,

me and Tim had a band together called the

Gits — with Tim, me, Ian Wallace on

the drums and Mel Collins on the sax. We

didn’t actually do any touring; we

just recorded, played and had fun.

You’re covering a lot of ground and

different styles on the new record

–

blues, country, rock, even a

little world.

Well, you could call it that. I prefer to

call it Spanish-influenced melodies.

Tell me how you came to write the title track.

I always liked the first solo album. It was

a bit of a landmark being my first solo album.

So I thought I’d write a song about

still being on the road to freedom. And I

go back and see the same guy there 40 years

ago. It’s the same rhythm as the original

song. That’s the main connection really.

And of course, freedom, as I said earlier.

I mean, freedom is a very relative thing

— it depends of where your situation

is in life. We’re always searching

freedom, but it’s not always the same

freedom you’re searching for.

Song of the Red Rock Mountain” is a

Spanish-influenced instrumental

you made

up on the spot while testing

a microphone.

I assume you were also playing

your guitar

at the time.“

That’s the one I was talking about

when you said “world music.”

I was in the studio, waiting for my tech

to come around and I’d bought a new

microphone. So I just plugged it in and thought

I’d check it out. I started to play

anything that came to my mind, and that beautiful

little song came up. I like it when that

happens. We just put it down in around 10

minutes, wondering, “Where did that

come from?” And it’s not premeditated.

Sometimes it’s like you grab it out

of the ether. You just reach up and, “Oh,

there’s a song. Let’s pull that

one down.”

You have “Love Like A Man 2,”

a remake of “Love like

A Man,”

which you recorded with Ten Years

After on

the band’s 1970 album Cricklewood

Green.

What prompted you to redo that

one?

I was just toying around with this cool rhythm,

kind of an R&B rhythm, an oldie, along

the lines of Smiley Lewis, “I Hear

You Knocking.” And I thinking I like

this rhythm, what can I put to it. And that

just kind of came up. I didn’t think

much of it at first actually, but as I worked

on it, it got better. So it’s on the

album.

Going back to 1973, On The Road To Freedom certainly showed a different side of the

Alvin Lee people knew with Ten

Years After.

Was that your intention?

Yeah, absolutely, that was 100 percent my

intention. I needed to make a change and

get away from what I thought at the time

was us repeating ourselves over and over

again. It’s funny because even the

lady who runs my website, she’s a big

fan. When she first got On The Road To Freedom, she gave it away because she was expecting

something like Ten Years After. Quite a few

people felt like that, but strangely enough

over the years that particular album has

probably sold more than any of the other

ones. It’s a long seller (laughs).

And you had Mylon LeFevre on it. Do you still

talk to him?

I do, yeah. He’s actually a minister

who runs a ministry out of Texas now. He’s

just written a book, which includes some

of the wild times we had.

Did you ask him to be on the new record?

I thought about it, but he’s living

an entirely different life. He doesn’t

actually sing anymore. He’s dedicated

himself to this church.

How about some of the other people who appeared

on the original? Mick Fleetwood?

Ron Wood?

No, there wasn’t a plan to do that.

It probably would have been a good idea,

but it was never my intention to make another

On The Road To Freedom. Just kind of nodding to the original On The Road To Freedom and saying I’m still on it. It’s

all different stuff. It’s not supposed

to be the same as On The Road To Freedom. It’s free music for the soul.

I read you actually got to know George Harrison

when Mylon brought him to your

house to make

the record.

I’d met George before. We’d met

quite a few times and had a few jam sessions.

But him being a famous Beatle and me being

a bit shy, I would never have dreamed of

asking him to come and play on an album.

It would have been a bit cheeky, really.

He’s got millions of fans. But Mylon

didn’t mind (laughs). He went over

and said, “Oh George, we want you to

play on the album.” Of course, George

was a musician and he didn’t think

twice about it. So he came.

The funny story is about the song “So

Sad,” which George wrote. Mylon said

to George, “I’d really like to

do one of your songs on this album.”

And George said, “Well, I’ve

done thousands of songs. I have the Beatles

songs and songs on my solo albums you could

do.” And Mylon, very cleverly, said,

“George, you played them so well. I

need to do one you haven’t done yet.”

And George said, “I’ve got this

one song I’ve been working on, which

I think might be a hit.” And Mylon

said, “I’ll take it!” (laughs)

That night, I finished building the studio

and actually, I was a bit late with that.

I had the whole band down and I had them

all putting up acoustic panels in the studio

to finish it off. When we finally finished,

Mylon, “Well, where do all the musicians

hang out?” And I said, “Speakeasy.”

So he put his zoot suit on and went down

to Speakeasy and came back three hours later

and said, “I got us a band, man.”

You obviously struck a chord with George

because you two recorded several

songs together.

Do you have a favorite you did

with him?

Yeah, “The Bluest Blues.” The

first guitar solo is George and it’s

really beautiful‛&one of the best

slide guitar solos I’ve ever heard.

I said, “I got this one that needs

a bit slide on it George.” and he said,

“I’ll be right over.” And

he played this beautiful, melodic solo. George

doesn’t jam like me. I’m a jammer,

I fire from the hip. But George writes a

song when he does a solo, he writes a tune

that becomes the solo. So he had this beautiful

melody and a really nice touch. It kind of

put me on the spot because I had to come

up with something to match it. I think I

did pretty good.

Back in the day, you were often cited as

one of the fastest guitar player

around.

Most definitely up there with

Jeff Beck,

Eric Clapton and Jimmy Page.

Do you hear

your influence in any of the

guitarists that

have come along since then? ;

Yeah, quite a bit actually‛&the

odd licks. That’s a compliment in a

way. I don’t mind that at all.

You listen to someone like Eddie Van Halen,

and you think he must have been

listening

to Alvin Lee.

I don’t know who he was listening to

(laughs). When I first heard Eddie Van Halen,

he was the one responsible for getting me

to start practicing again. I first heard

Eddie do a solo, and I thought, “Whoa‛&I

better get my guitar out and start practicing.”

You have a song on the new record called

“Back in ’69,”

and I wanted

to ask you about a particular

Sunday in 1969

when you played this gig in upstate

New York.

Where’s that?

This little gig called Woodstock.

Yeah, that was a nice little gig..

I understand you had technical problems,

but when it came to “I’m

Going

Home,” everything sort

of fell in place

and they were able to film the

performance.

That’s right. We just went right on

after the rain storm. There was a lot of

humidity in the air and all the guitars went

madly out of tune and we actually had to

stop. The song was “Good Mornin’

Little School Girl” and I had to stop

it and say, “Sorry‛&excuse

me‛&I want to get us in tune here.”

At that point, it was looking like a disaster.

But as you see from the movie, we manage

to get back on course.

Did you have any idea that that would be

a game changer for you?

Well, nothing happened for a year. We continued

to play the Fillmore and the Boston Tea Party‛&two

to three-thousand seaters. It wasn’t

until the movie came out that suddenly we

found ourselves playing Houston Coliseums

and Madison Square Gardens.

I was watching the Blu-ray last night and

relived your Woodstock performance.

And when

you’re done, you pick up

a watermelon.

Where on earth did that watermelon

come from?

It just sort of rolled on. I didn’t

see where it came from. It just rolled onto

the stage. I don’t know why or what

was going through my mind. I just casually

threw my guitar into the drum kit and picked

up this watermelon (laughs). At all the gigs

after the movie came out — we were

playing big festivals and stuff like that

— and (during) the last number, about

200 watermelons were all bobbing away in

the audience. And by the end of the last

number, the whole stage is covered in watermelon

(laughs).

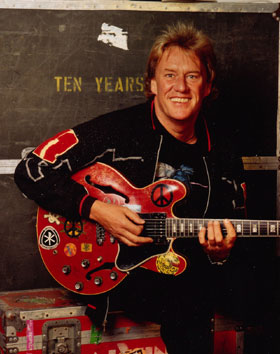

You obviously had great success with Ten

Years After, and have played

off and on with

the other guys over the years.

Do you foresee

a time when you might play with

them again?

It’s not really likely. We tried it

a few times. And it usually ended in —

what shall I say — discontent (laughs).

We put the band together again in 1990 and

did a world tour, and we’ve done it

two or three times since then. It’s

a bit like going on tour with four ex-wives.

It’s great at first, but then you have

one little bitch and then everyone’s

going, “There you go again. This is

the trouble with you.” All the baggage

comes out, you know.

Outside of Ten Years After, you have played

with some of the greatest musicians

on the

planet. There were all the guys

on your first

album — Steve Winwood,

Jim Capaldi,

Boz Burrell, Ron Wood, and George

Harrison.

And then in 2004, you got together

with Scotty

Moore and D.J. Fontana (members

of Elvis

Presley’s original backing

band) and

made Alvin Lee in Tennessee.

That must have

been a great experience.

It was fantastic. Scotty and D.J. were playing

in London, promoting a new album or something.

Every guitarist I know got invites. Gary

Moore was there. We had a jam session and

I was first up. I did this medley of Elvis

hits. It was great fun. I went back to being

like 14, 15-years-old when I was listening

to those records. Suddenly, there was those

guys playing behind me and it gave me such

a buzz. I said, “Is there any chance

I can get you guys in the studio and make

an album?” And they said, “Yeah,

sure.”

So I went off and wrote some appropriate

songs. I called up Scotty and said, “I’ve

got some songs ready — and where would

you like to record?” And he said, “Well,

we’ll record at my place,” which

was fantastic. I couldn’t have wished

anything more. He has a house with a built-in

studio. Actually, it’s a studio with

an adjoining kitchen and bedroom. He’s

got all his Elvis memorabilia there and all

his great guitars. I was like a kid in a

sweet shop.

Did they tell you any secrets about Elvis?

Tell you any good stories?

Oh yeah. There were a lot of great stories.

You guys did “I’m Going Home,”

which is really fantastic. How

did you like

revisiting that one?

That was fun. Pete (Pritchard) the bass player‛&it

wasn’t on the plan, but Pete said,

“Let’s do 'Going Home,' it'll

be great.” And I said, “Ok, we’ll

give it a shot.” And we played it once,

and it was fantastic. D.J. Fontana might

not be the cleverest drummer, he might not

be doing all the drum fills, but he’s

got such a rhythm going. He’s like

a train behind you. He just pushes you along.

Not too fast, not too slow. He’s got

the beat, he’s got the pocket.

So getting back to you Still On The Road To Freedom, do you have any plans to play some shows

or do a tour behind it?

I’m hoping to. There’s no plans

as such yet. I don’t actually tour

anymore in the old sense of like doing 12

weeks on the road. I’m more likely

to show up at the odd festival. That’s

the kind of thing I like to do. There’s

always a good chance of that. I like to do

open air festivals these days. It’s

just a nice vibe to look up and see the sky.

It’s much better than being inside.

You don’t have the acoustics to battle

against.

When was the last time you played here in

the States?

That would be 1999. It would have been the

Woodstock anniversary gig at Bethel Woods.

“I’d Love To Change The World”

has a certain relevance in these

trying times.

Always. It’s never lost its relevance

actually. It’s harder to change it.

Every year, it gets harder and harder.

Would you still love to change the world?

Well, that’s the point of the song:

I’d love to change the

world, but I

don’t know what to do and

I’ll

leave it up to you. I’m

just saying

the world does need changing.

I’d love

to do it, but I haven’t

got the talent.

I don’t think I’m

a world changer

(laughs).

Musoscribe with Bill Kopp

Off the Road Yet On the Road: A Talk with

Alvin Lee,

Guitarist Alvin Lee first rose

to international

prominence with his band Ten

Years After.

The band's performance of I'm

Going Home

is a highlight of both the Woodstock

film

and the accompanying soundtrack.

The band

enjoyed a number of hits - most

notably 1971's

I'd Love to Change the World.

In 1973 Lee

stepped out for a solo album,

On the Road

to Freedom. He has remained active

since

leaving TYA, with a relatively

consistent

string of solo albums. His latest

record

bears echoes of his first solo

release, and

showcases his mastery of a wide

array of

styles. Recently, Alvin spoke

with me from

his home in Spain. - bk

Bill Kopp: The first thing I notice when

listening to Still On the Road

to Freedom

is perhaps the most obvious,

but it's also

remarkable: Your voice. Your

singing voice

as heard on this new album: it

doesn't sound

a bit different from the way

you sounded

on I'd Love to Change the World

or I'm Going

Home, forty years ago. Do you

do anything

to keep your voice in shape?

Bill Kopp: The first thing I notice when

listening to Still On the Road

to Freedom

is perhaps the most obvious,

but it's also

remarkable: Your voice. Your

singing voice

as heard on this new album: it

doesn't sound

a bit different from the way

you sounded

on I'd Love to Change the World

or I'm Going

Home, forty years ago. Do you

do anything

to keep your voice in shape?

Alvin Lee: No. I'm afraid I haven't

any secrets

to divulge about that. That's

just the way

it is; genetics, probably.

BK: There's always been a strong early rock

'nroll/rockabilly sensibility

to your original songs. I'm a Lucky Man, on

the new record, for example,

could easily

be a cover from 1957.

AL: It almost could have been

recorded in

1957. I tried to get the authentic

sound

on that one; I was quite pleased

with it.

BK: On songs like that, do you

set out to

write in a particular style,

or do you just

write a song first and then apply

a particular

style to it?

AL: The style generally comes

along with

the song. That one has pretty

much of a rock'n'roll,

"Whole Lotta Shakin" rhythm.

So I get the

rhythm going, and then I think,

"What am

I going to say in this one?"

BK: One of the trends that I notice among

many artists who came to prominence

in the

60s and 70s is a tendency to

- how can I

put it - stop rocking. One can

go too far

in one direction or another:

you could get

all acoustic and mellow, or you

could rock

out 100% of the time and come

off a bit ridiculous.

AL: That's always been the dilemma,

hasn't

it? That's why I did Still On

the Road to

Freedom, because I'm right in

the middle,

between the two.

BK: You balance the two extremes nicely on

this record. You have contemplative,

acoustic

tracks like "Walk On, Walk

Tall,"

but they sit nicely alongside

the rockers.

Was that mix, that variety, by

design?

AL: I've always been keen to

not be obsessed,

to not get stuck with styles.

Because I like

so many different styles of music.

I like

things by Chet Atkins, Scotty

Moore, Chuck

Berry, Django Reinhardt, Wes

Montgomery.

All those guys have been an influence.

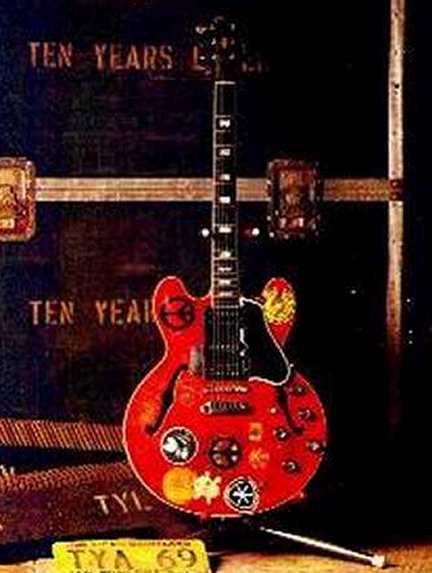

BK: On 2009's Saguitar, the cover art shows

that iconic Gibson that's become

so closely

associated with you. Do you still

use the

ES, and - besides acoustic guitars

- what

other guitars do you use?

AL: I don't use that one, any

more. Which

is quite sad: unfortunately,

it's locked

up in a vault. Ever since somebody

offered

me half a million dollars for

it! I wrote

in the song "Once There Was a

Time" [on Ten

Years After's 1971 LP A Space

in Time] that

I'd never sell my guitar. And

I've kept to

that one.

I've got several guitars. Gibson

made an

anniversary replica of the Woodstock

guitar;

they made a hundred hand-built

ones, and

then they put it into production.

There's

quite a few kicking about. But

I like to

use off-the-shelf guitars; if

anything happens

to one, you can replace it easily.

Some of the bands I've seen,

they take fifteen

guitars on the road. A hundred

thousand quid

worth of guitars onstage; it's

madness. It's

all very well, but I prefer to

play just

one guitar, and try to make it

do as many

things as I can.

BK: What sort of gigs are you doing in support

of the new album?

AL: I did a gig about a month

ago in Holland,

at a festival. It was really

great; the Dutch

people are really cool. The festival

had

a huge arts section, with paintings,

dancers.

A lot of stuff going on. Before

that, I was

busy finishing the album, so

I hadn't had

a gig - and the band hadn't played

together

– in eight months. And of course

at a festival,

there's no sound check; there

are bands playing

all day. So went onstage cold,

not having

played for eight months, and

then we actually

played one of the best gigs in

any of our

lives!

I think that's because, when

you play every

night, you can start to go into

"auto." The

thing is to play as much as you

can, but

to still enjoy it. And of course

in the 1970s,

Woodstock having been a big deal,

I was playing

five, six, seven nights a week.

You do that,

and you can start becoming a

traveling jukebox:

stand us up, plug us in, and

we'll blast

out the same old set.

Bill Kopp: The title and cover art of your

new album Still On the Road to

Freedom overtly

reference your 1973 collaboration

with Mylon

LeFevre. Beyond the text and

visuals, what

is the connection between the

two records?

Alvin Lee: There's not really

a connection.

The only connection is that in

1972 I wrote

the words to "On the Road

to Freedom,"

and what I'm saying now is that

I’m still

on that road. I still haven't

got there.

There’s only that one song that's

relevant

[to the old record]. The rest

of the album

is new music, the sort of things

that comes

out as my music today. I'm not

trying to

do a sequel, a follow-up.

BK: If someone asked me to describe

the music

on Still On the Road to Freedom

by applying

a single genre label to it, I

couldn't do

it. There's country rock, blues,

Bo Diddley

style rock, quiet acoustic numbers,

on and

on. Do you think that - in an

ironic way

- that the end of the record

industry as

we used to know it has meant

that artists

are free to follow their muse

where it takes

them, rather than being expected

(or required)

to turn in twelve songs in a

single style?

AL: It's a nice thought, but

actually no.

To get that freedom- and I went

for it in

1973 - I was giving up a lot.

I was giving

up the road to fame and fortune.

The road

to freedom was for my health,

anyway.

But record companies today, if

you sign with

a big record company, they practically

own

the artist. They tell them where

to go, what

TV [shows] to do. It's actually

worse than

it's ever been. But of course

there are more

bands playing on a smaller level.

They have

record companies that will pretty

much put

something out if they like it.

They're not

dealing in hits any more. And

they're not

spending $200,000 on promotion.

So, yes and no. There is more

freedom for

bands to record; it's something

I've always

fought for. The record company

comes and

says, "We want an album

that's the same

as the last one," and I

say, "Tough.

I'm gonna send you one that I

like. And I

hope you like it. If not, don't

release it."

BK: When I was a kid, I often heard the label

"fastest guitar in the west"

applied

to you. I don't remember now

where I heard

that. But while you don't always

do so, you

can play really fast, like on

the new track

"Back in '69." Back

in the day,

do you think that there was an

expectation

- when people came to see and

hear you with

Ten Years After - that you'd

have to play

like that? To show just that

one side of

your talent, the flash side?

AL: To a degree, that was a part

of the freedom

I was searching for, too. They

used to call

me Captain Speedfingers, too;

I didn't take

all that seriously. There were

and are many

faster guitarists than me. People

like John

McLaughlin and Django Reinhardt:

unbelievably

nimble. But with me, I think

it's because

of the way I play. Light and

shade. I'll

play it cool, and then I'll hit

some rocket

riffs. And that makes the rocket

riffs sound

more effective.

I've been to see some great guitarists

-

I won't mention any names - who

clearly must

practice twelve hours a day.

But after ten

minutes, you've heard everything

they've

got.

BK: On Saguitar you played most of the instruments

yourself. On this latest, you

still do a

lot of the work, but you have

brought in

players for most tracks. How

do you think

that changed the nature of the

music?

AL: I think the new one has a

more realistic

feel. On Saguitar, I was "concocting"

a real

feel. I used computer drums and

did play

most of the instruments myself.

I have always

had a fascination with Les Paul,

the way

he used to overdub his guitar

fifty times.

So it was partly that: trying

to see how

real a sound I could get by myself,

making

it on the computer. And I think

it was pretty

good; I spent a lot of time and

effort to

get the right feel, to capture

that interplay

of the various instruments. On

the new album

I've got Pete Pritchard on the

bass, and

Richard Newman on drums. So it's

got more

of a live feel to it.

BK: Are there any plans at all

for some North

American dates in support of

Still On the

Road to Freedom?

AL: None planned as of yet, but

I'll play

anywhere someone wants me. It's

hard, though.

You''ve got to get visas, air

tickets. It's

a big deal. You can't just pop

over and do

one gig. That's what I do in

Europe, though:

I do a festival on a Saturday

night - or

any night, basically - and keep

my hand in

that way. But those tours of

five or six

nights a week, I'm not up for

that any more.

It kills off the fun of making

music. Touring

with a rock 'n' roll band becomes

boring,

and then you've got a big problem

on your

hands. I never really wanted

to be a rock

star...

...Actually, I don't want to

lie. When I

was really young, I wanted to

be a big star

and make lots of money. But it

seems that

the reality doesn't ever quite

match up to

the dream. Once you get there,

it's not just

about having fun. It's a lot

of responsibility,

and a lot of pressure. That builds

up on

you, and sometimes you turn to

drink and

drugs. And those don’t make things

any easier.

BK: Your discography notes that you "do

not play with the band currently

recording

as Ten Years After." Is

this one of

those situations where ownership

of the band

name is contested, or is it something

else,

something more cordial?

AL: Well, it could have been

cordial. But

I was really not happy with what

they did.

It was behind my back, and all

very sneaky.

But those guys spent as much

time on the

road all those years ago as I

did, so they

have some right to do it. I just

wish they

had called it something else,

like Ten Years

After II, or something like that.

BK: Maybe Forty Years After…

AL: I think that's what it is

now, isn't

it?!

Guitar Afficianado

August 20th, 2012

By Damian Fanelli

From a guitarist's perspective,

the 1970

Woodstock film, which documents

the highs

and lows of the August 1969 Woodstock

Festival,

has several highlights.

There's Jimi Hendrix's immortal

take on "The

Star-Spangled Banner"; a

lengthy, mind-blowing

performance by newcomers Santana;

and Pete

Townshend's high-flying Gibson

SG acrobatics

with The Who, to name just a

few.

But for a full-on blues-rocking experience,

there's no beating Ten Years

After's adrenaline-fueled

reading of "I'm Going Home."

The

performance, an intense nod to

vintage blues

and '50s rock and roll, featured

the lightning-fast

fretwork of Ten Years After frontman

Alvin

Lee.

But for a full-on blues-rocking experience,

there's no beating Ten Years

After's adrenaline-fueled

reading of "I'm Going Home."

The

performance, an intense nod to

vintage blues

and '50s rock and roll, featured

the lightning-fast

fretwork of Ten Years After frontman

Alvin

Lee.

"The solo on the movie sounds

pretty rough

to me these days," Lee told Guitar

Aficionado

late last week. "But it had the

energy, and

that was what Ten Years After

were all about

at the time."

The performance made stars out

of the British

band, which led to more festivals,

a label

change and their biggest hit,

1971's "I'd

Love to Change the World."

Although

the band still tours, they do

it without

Lee, who has found happiness

as a solo artist,

carefully choosing a handful

of festival

performances per year.

Lee is releasing a new studio

album, Still

On the Road to Freedom, August

27 via Rainman

Records. The title is a reference

to his

1973 album with Mylon LeFevre,

On the Road

to Freedom.

Lee recently took some time to

discuss his

new album and his gear over the

years, including

his famous Woodstock-era "Big

Red"

ES-335.

GUITAR AFICIONADO: How often

do you pick

up a guitar and play these days?

Pretty much every day. I write

and record

all the time; it's my hobby and

my passion.

I have a Spanish gut-strung guitar,

a Dobro

resonator and a Line 6 Variax

hanging on

the wall, and they all get played

regularly.

The new Variax is very impressive.

Your new album covers a lot of

ground, revisiting

the past, looking to the future

and offering

a myriad of different sounds.

Was that intentional?

It kind of evolved from luck

and circumstance,

as if it were trying to get out

on its own.

I originally had 33 songs to

choose from.

As they developed and evolved,

I picked out

the ones that showed the most

promise. As

I continued to work on them,

I realized they

pretty much went through most

of my musical

influences and styles over the

years, so

from then on it became a time-warp

concept.

What gear did you use on the new album?

Mainly a Gibbo [Gibson] ES-335

and a Martin

acoustic. I used a Wal bass and

a Gretch

baritone guitar for bass, as

well as Pete

Pritchard's Music Man and a doghouse

double

bass called Charlie Boy.

Amp-wise, I used a Wem 15 Dominator

and a

very old Yamaha I bought from

Mick Abrahams.

I also used the original Pod,

which is better

than the new ones, as a pre-amp

into a Fender

Champ and Mustang. Plus Guitar

Rig and Amplitude

and too many others to mention.

On "Listen to Your Radio

Station,"

I used the Metalizer pedal Leslie

West gave

me. It's quite radical and has

to be tamed,

as the slightest finger twitch

comes blasting

through the amp. Leslie came

up to me at

the Night of the Guitars sound

check and

said, "Alvin, you're a damn

fine guitarist,

but you're not loud enough."

He then

proceeded to give me loudness

lessons. I

like Leslie's playing. He has

excellent rock

and roll phrasing.

What is some of your more prized gear, the

things you’'d rush to save from

a fire, for

instance?

My Martin acoustic. I bought

it in New York

in 1970, and the guy gave me

a receipt for

$150 for the customs. I walked

into the "something

to declare" channel and

showed the guy

the receipt. He opened the case

and said,

"A Martin guitar with Grover

machine

heads for $150?" I had only

found the

musical instrument expert customs

man.

Four hours later, I walked out

with my Martin

having paid a fine, a penalty

and having

had to buy it back. Ever since

then, I’'ve

used the "nothing to declare"

channel.

On the album opener, the title track, you

can immediately tell it’'s Alvin

Lee on guitar

- not just because of your note

choices but

also your sound. How would you

say your sound

has evolved over the years? Are

you still

using that Woodstock ES-335?

I've still got the original Woodstock

335,

but, sadly, I don't use it these

days as

it has become too valuable. She's

now in

a vault since some loony offered

me half

a million dollars for her.

Sound-wise, I never use pedal

effects on

stage and seldom in the studio.

I prefer

to get my overload sustain from

having the

Marshall cranked up high, then

by turning

the guitar down to 5 or 6, you

get a nice

clean jazz sound. The crunch

comes in around

7 or 8. What else do you need?

How involved were you in the creation of

Gibson's Custom "Big Red"

Alvin

Lee ES-335?

That all came about because of

Pat Foley

at Gibson. He asked me if I’d

be interested,

and I said of course, it’s a

great compliment.

So he came over to England to

photograph

and measure Big Red, and Gibson

pretty much

took it from there. I had no

involvement

until I got the first prototype.

Then I made

a few changes, which resulted

in my getting

several more prototypes. Now

I’ve got a whole

bunch of them — a gaggle of Gibsons.

Who were your favorite guitarists

when you

were growing up?

My favorite country blues player

was Big

Bill Broonzy. City blues was

Freddie King,

but I liked them all — Muddy

Waters, John

Lee Hooker, Ralph Willis, Lonnie

Johnson,

Brownie McGhee and the three

Kings, B.B.,

Albert and Freddie. Jazz-wise,

I listened

to Django, Barney Kessel and

Wes Montgomery.

Charlie Christian, Benny Goodman’s

guitarist,

was a great influence on my swing

phrasing.

My all-time favorite rock and

roll players

were Scotty Moore, Chuck Berry

and Franny

Beecher, and I listened to the

country playing

of Merle Travis.

Did you admire the other great

fast bluesman

of the time, Johnny Winter?

Strangely enough, I wasn't into

fast guitarists.

I preferred Peter Green's subtle

touch. I

saw him with John Mayall's Bluesbreakers

at the Marquee Club in London

and was very

impressed. He was the only guitarist

I've

ever seen to turn the volume

control on his

guitar down during a solo.

What kind of delay/reverb, amp and overdrive

did you use on the solo on "I'd

Love

to Change the World"?

As far as I remember, it was

a Wem Dominator

used as a pre-amp into the old

Marshalls.

I had the Wem 15-Watt power amp

padded down

to guitar input level. The echo

was an EMT

plate.

The first time I saw the Woodstock film,

I was completely knocked out

by Ten Years

After's performance of "I'Going

Home."I

remember thinking I'd never seen

a blues/rock

guitarist play that fast before,

at least

in the context of 1969. And then

there was

the intensity of the band. It

was a bit chaotic

yet completely hemmed in by a

rock-solid

beat. Where did that come from?

You’re obviously a man of very

good taste!

Seriously, though, I never really

tried to

play fast. It kind of developed

from the

adrenalin rush of the hundreds

of gigs I

did long before Woodstock. They

called me

"Captain Speedfingers"

and such,

but I didn't take it seriously.

There were

many guitarists faster than me

- Django,

Barney Kessel, John McLaughlin

and Joe Pass

to name a few.

The solo on the movie sounds

pretty rough

to me these days, but it had

the energy,

and that was what Ten Years After

were all

about at the time. However, I

often wonder

what would have happened if they

had used

"ICant Keep From Crying"

in the

movie instead of" I'm Going

Home."

Anything else you'd like to add?

Rush out and buy Still On the

Road to Freedom!

Huffngton Post

A Conversation With Alvin Lee

Mike Ragogna: Hello Mr. Alvin

Lee, guitar

god from Ten Years After and

your own solo

career. You've got a new album,

Still On

the Road to Freedom, the title

being a play

off of one of your classic albums.

But first,

how're you?

Alvin Lee: I'm fine. How are

you?

MR: Dandy. And no, you're not

part of Canned

Heat. (laughs)

AL: No, but that's okay, they're

a great

band. We used to play with them

in the early

sixties in Golden Gate Park,

and they came

to England and they were good

buddies of

mine.

MR: Right. Remember any of those

old shows?

AL: I can remember Golden Gate

Park because

it was a free concert. It was

really cool

in the height of the sixties

and all that.

I went back to The Bear's house

one time

and he had this great collection

of '78 records

and we spent the whole evening

listening

to the John Lee Hooker, Muddy

Waters, and

Big Bill Broonzy and the likes.

I really

got along well with those guys.

I stayed

in touch with Fito the drummer.

He is one

of the best shuffle drummers

in the business.

MR: Alvin, who are some of your

heroes, the

people who inspired you?

AL: I was really lucky, my dad

was an early

inspiration. He was an avid music

collector

of ethnic music. He had things

like an album

called Murderous Home, which

was prison work

songs. He also brought Bill Broonzy

back

to the house one time after he

played a gig

in Nottingham. Big Bill was a

big influence

on me. Once when I was 12 years

old, I sold

my clarinet and bought a guitar

the next

day. Big Bill, Ralph Lewis, Lonnie

Johnson,

Ledbelly, Muddy Waters, Brownie

McGhee, Freddy

King...I liked all those guys.

I also liked

the jazz side of Johnny Christian,

Wes Montgomery,

Barney Kessel, Django (Reinhardt).

And, of

course, rock 'n' roll. Scotty

Moore is my

big favorite. Chuck Berry. Also,

a bit of

country I used to listen to like

Chet Atkins

and Merle Travis. They were all

influences.

There are probably a lot of others,

really.

I've played a little classical,

too. Segovia,

as well. All around influences.

MR: When you're playing live

or recording

new projects, do you ever find

yourself whipping

out a classical guitar or doing

more jazz?

AL: I do little vignettes of

it between the

numbers. I play a little bit

of "Cry

Me A River" and country

ho-down thing,

like a Merle Travis kind of thing.

I just

kind of throw those in for fun.

I don't actually

do any jazz songs as such in

the sense that

I keep nodding my head and playing

intro

bits like that. (laughs)

MR: Let's talk about the new

album, Still

on the Road to Freedom. In order

to have

context, is it best to talk a

tiny bit about

the original, On the Road to

Freedom?

AL: It's not as much a sequel.

It's a new

album. The word "freedom"

came

out of the one song. I wrote

that one song,

"Still on the Road to Freedom,"

so that became the theme for

the album, and

then I thought it would be cool

to have a

cover that looks a bit like the

original

and let people know I'm still

on the road

to freedom. It's always been

something I've

been searching for--freedom.

It's a very

relative thing. It means different

things

to different people. Musical

freedom has

always been very strong for me,

something

to strive for, to be able to

play the music

you enjoy playing rather than

playing music

that other people want to hear,

which I find

rather shallow and unrewarding.

So I make

albums I like and I put them

out and hope

other people like them and that's

a kind

of freedom in itself.

MR: Given you're talking to me

at KRUU, the

Midwest's only solar-powered

radio station--had

to throw that in--I especially

like "Listen

to Your Radio Station."

(laughs)

AL: Thought you might like that

one. "It's

the coolest music across the

nation, all

good stuff and all for free,

it must be cool

if they're playing me."

It's something

I have a feeling on. These days,

lots of

people have iPods and tend to

be listening

to their favorite music but it's

the same

music over and over again. I

strongly encourage

listening to the radio to hear

something

you haven't heard before. It's

a very healthy

thing to do. It's strange, unless

you reload

your iPods every couple of weeks,

you're

listening to and recycling the

same music

all of the time. I'm serious.

Listen to your

radio station. One thing that

does annoy

me with radio stations, I hear

something

and think, "Oh this is good,

who is

this?" And I wait for the

end of the

record, they give the station

ID and the

time. I know that, but they don't

tell me

who the artist is. I find that

quite annoying.

MR: At our radio station, we

do announce,

plus you can see all of the titles

online.

AL: God bless the digital age.

Must be a

cool radio station.

MR: Indeed, sir! Let's get the

story on "Song

of the Red Rock Mountain,"

like what

inspired you to write it?

AL: I'm actually getting good

feedback on

that one. It's off the wall.

It's not rock

'n' roll by any means; it has

a Spanish flavor.

Strangely enough, I was sitting

in the studio

waiting for my tech to come and

I had to

sort out some wiring or something,

so I thought

to test this new microphone.

I stuck the

microphone up, picked up my Martin

guitar

and, basically, it practically

came out instantly.

I got that little rhythm going

and the very

simple tune. "That was quite

nice,"

I thought. Then I thought maybe

I'd go back

to it and try to do it properly.

I went back

to it about twenty times and

it never got

better than that first time.

It's one of

those magic moments.

MR: Where does your creativity

come from?

AL: I don't know. That's the

beauty of creativity.

It comes from the ether. I like

to think,

sometimes, it's like I haven't

written it,

it's more like I just reached

up and grabbed

it from somewhere. That song,

"Song

of the Red Rock Mountain,"

is one of

them. I recorded it and thought,

"Where

did that come from?"

MR: And there's "Back in

'69."

AL: "Back in '69" was

kind of a

Bo Diddley rhythm I had that

worked out with

the band as a backing track.

I wasn't happy

with the words, they were too

ordinary. It

was like, "My baby been

done left me

and left me waiting at the station."

So I looked through my book of

poems and

that actually was a poem I wrote

just to

fit the song perfectly, back

in '69.

MR: Now for those Ten Years After

stories.

AL: It was great. The sixties

were a great

period. I love the early days

of Ten Years

After playing around the clubs

in London.

I remember we first came to America,

it was

about 1968. We visited Haight-Ashbury

and

everywhere. I was actually really

into America.

I loved James Dean and American

cars and

American music, so I was really

thrilled

to get there. Great memories

up until, strangely

enough... A lot of people say

the Woodstock

movie made Ten Years After. But

actually,

it was the beginning of the end

for me because

we stopped playing clubs like

The Fillmore

East and The Fillmore West, The

Grande Ballroom

and The Boston Tea Party, those

really cool,

kind of rock 'n' roll gigs with

two or three-thousand

people. After the movie came

out--not after

the concert but after the movie

came out--suddenly,

we were catapulted to Madison

Square Garden,

Sam Houston Coliseum and hockey

arenas, the

worst places to play in the world.

They were

just dreadful places to play.

The fun came

out of it for me there, and I

realized I

didn't want to be a rock star,

I wanted to

be a working musician. So that's

one of the

roads to freedom I took right

there and then.

MR: Nicely said.

AL: At first, it was great. The

band went

for eight years, and it was a

great band

and I really enjoyed it. But

there comes

a time to move on and do other

things.

MR: One other part of your history

is that

you were in The Jaybirds, of

course. The

Jaybirds were in that same circuit

The Beatles

were in.

AL: We played The Star Club in

Hamburg. That

was quite a trip. I just turned

17 years

old and found myself in the land

of sex,

drugs, rock 'n' roll, prostitutes,

and gangsters.

It was a crash course in rock

'n' roll, I'll

tell ya.

MR: Has much changed since then?

AL: In Hamburg? Well, a lot actually.

They

have different prostitutes and

gangsters,

but they're all still there.

MR: Let's get back to your solo

career. You've

had a few solo albums and some

wonderful

guests on those projects such

as George Harrison.

You guys were pals?

AL: Yes, George was a good friend.

I was

a very lucky guy. I knew him

and I used to

hang out with George quite a

lot. We were

very good after hours friends,

you know.

He would make serious music and

I'd make

serious music and when all those

guys had

gone home, we'd get together

and just have

fun playing nonsense and playing

whatever

we felt like. He had his studio

all set up

with all of this amazing gear

and equipment.

We'd go in and try to get it

working and

have a lot of fun. (laughs) George

was a

musician; he liked to play, just

like anybody.

So one time, I asked, "Any

chance of

a slide guitar on this song?"

He said,

"I'll be right over."

MR: Nice.

AL: Good man.

MR: One of your more beloved

tracks is "The

Bluest Blues," that a popular

reviewer

called, "The most perfect

blues song

ever recorded."

AL: That's very nice. I kind

of think B.B.

King's "The Thrill is Gone"

is

a little ahead of that, but I

appreciate

the gesture.

MR: There's your project Alvin

Lee in Tennessee

from back in 2004. How did it

come about?

AL: Scotty Moore and D.J. Fontana

came out

over to England. They were playing

a launching

of an album gig at Air Studios

in London.

They invited me to come down

and have a jam,

and I wasn't going to miss that

one because

Scotty is the boy for me. I got

up there,

I did a rock 'n' roll medley,

"Blue

Suede Shoes," "Rip

it Up"

and "Hound Dog." It

was just great.

What particularly thilled me

was D.J. Fontana

playing behind me. I turned around

and I

said, "Let's start with

'Rip It Up,'"

and they all sat there. And I

said, "C'mon,

ch-ch-ch-ch-ch..." D.J.

said, "Oh,

yeah!" and he started playing

that intro.

That's because D.J. started it!

It was great

just hearing that music, those

drum fills

and those rhythms that I cut

my teeth on

all those years ago, and there

I was playing

with these guys. Afterwards,

I said, "Any

chance to get you guys in a studio

to make

an album together?" They

said, "Yeah,

love to." So I shot off

and started

writing songs for that project.

MR: I think I have a sense of

what the word

"freedom" means to

you. It's the

freedom to express yourself creatively,

isn't

it.

AL: That's right. Yes, that pretty

much pours

it in the bucket.

MR: Alvin, what information or

advice might

you have for new artists?

AL: New artists? Actually, these

days, my

advice is to throw away your

PlayStation

and pick up an instrument. I'm

a bit of a

PlayStation junkie myself, but

had I had

a PlayStation or a computer as

a teenager,

I probably would have never played

guitar.

If you put the time into playing

an instrument

that you put into playing on

your PlayStation,

you could be playing in a band

within a year,

and that, it seems to me, is

a much better

way to go.

MR: That's wonderful advice.

The same might

be applied to spending time on

Facebook?

AL: Yes, absolutely. And surfing

the old

net and all that. There are many

things like

that these days. I was lucky

when I was younger.

There were only records, that

was it. Records

and films were the only thing.

Records were

so big. You'd buy a record, you'd

go home,

you'd treasure it and play it

again and again.

It's kind of a bit sad these

days that it's

almost like a disposable thing.

My advice

is lock up your PlayStation and

pick up your

guitar.

MR: People seem to be moving

from thing to

thing so quickly, maybe searching

for that

instant gratification.

AL: Yeah, it's getting faster

and faster,

isn't it?

MR: Yeah, no savoring. Some last

words on

your new album. It basically

was recorded

with Pete Pritchard and Richard

Newman.

AL: Yes, and I have Tim Hinkley

on keyboards.

He's been with me for many years.

He was

on the original On Road to Freedom

album

and with me on my second In Flight

album.

He is one of my favorite keyboard

players.

He's in Nashville now. He came

over from

Nashville to play on the album,

which was

pretty cool.

MR: The way you recorded Still

on the Road

to Freedom, was it you all playing

together

with just a little overdubbing

later?

AL: Some of it was that. Some

of it was just

me and Richard on the drums.

On some of the

songs, I find it great just to

play with

the drummer because then you

can change the

chords as you go. You can stick

in a chorus

when you feel one is due and

stuff like that.

So I did quite a lot, just about

half, with

just the drums and me, and had

Pete put the

bass in afterwards. But some

of the more

rock-y ones, they were pretty

much live.

MR: You'll be touring, right?

AL: Yep. Hopefully. I'll play

anywhere that

will have me. I won't be doing

any 10-week

tours these days. I love to play,

but I'm

just not into that mad kind of

traveling

anymore. I've done a few million

miles already.

MR: Alvin, you are a guitar hero

to many,

many people. Are you aware of

that?

AL: Well, kind of. I don't necessarily

believe

it. I've got my heroes and other

people have

their heroes. I consider myself

a pretty

cool guitarist but not really

anything especially

brilliant. But that's not for

me to say.

If other people like it, that's

great, and

I thank them very much.

MR: Beautifully said. Alvin,

thank you so

much for the time, this was special.

AL: Thank you very much, Mike,

I enjoyed

it. Keep on pumping those watts.

Rocksquare

Interview: Alvin Lee talks about

his new

album, Ten Years After, and how

he’d still

love to change the world

At age 67, guitarist Alvin Lee still has

faster fingers than a pickpocket. For an

example of Lee’s dexterity, listen

to the title track of his new album, Still on the Road to Freedom. Over the space of four minutes, the guitarist’s

fingers hopscotch across the fretboard for

several exciting, blues-based solos in which

he shows off his formidable technique of

stinging vibrato, wailing bends, and nimble

pull-ons and pull-offs.

But then, Lee always was a fleet-fingered

fellow. When the Nottingham-born guitarist

founded Ten Years After during the British

Blues Boom of the mid 1960s, his virtuosity

was remarked on even back then. Yet, when

modern rock writers recall that halcyon era,

they sometimes neglect to mention Lee’s

name alongside the likes of Jimmy Page, Eric

Clapton, Jeff Beck and Peter Green. The sleeve

notes to Still on the Road to Freedom offer one possible explanation for why that

is. “In 1972 after Woodstock had catapulted

Ten Years After into the Rock Arenas, I decided

to take the road to freedom rather than the

road to fame and fortune,” writes Lee.

It was a courageous move. Between 1968 and

1974, the blues-rock band released popular

albums such as Undead, Stonedhenge and Cricklewood Green and scored hits such as “I’d

Love to Change the World,” “Hear

Me Calling,” “Love Like a Man,”

and I’m Going Home” (the latter

immortalized during the band’s star-making

performance at Woodstock). But Lee was less

than enamored by record company pressures

and the more pop-oriented direction the band

was pursuing. In 1973, Lee stepped away from

his day job to collaborate with southern

gospel singer Mylon LeFevre for a country-rock

record On the Road to Freedom, an album that featured guest players such

as George Harrison, Ron Wood, Mick Fleetwood,

Jim Capaldi and Steve Winwood. On the Road to Freedom heralded the end for Ten Years After, though

the band did release Positive Vibrations in 1974 and, later, during one of its handful

of short-lived reunions with Lee, it attempted

a comeback album in 1989 titled About Time. (Since 2003, the remainder of Ten Years

After has continued to record and tour without

Lee.)

Following his tenure in Ten Years After,

Alvin Lee has released over 20 albums, most

notably Zoom, I Hear You Rockin’ (a.k.a. 1994) and Alvin Lee live in Tennessee, a 2004 recording that included a guest

appearance by Scotty Moore, the guitarist

whose work with Elvis Presley inspired Lee

to become a musician. (Ten Years After was

established in 1966, a decade after Elvis’s

breakthrough—hence the band’s

name.)

Still on the Road to Freedom, released August 28, isn’t exactly

a sequel to On the Road to Freedom. Though the album touches on that album’s

country blues on “Save My Stuff,”

the new record’s 11 tracks are truly

diverse and reflect Lee’s wide-ranging

musical interests. It spans from the flamenco-tinged

instrumental “Song of the Red Rock

Mountain,” to the traditional ’50s

rock ’n’ roll of “I’m

a Lucky Man,” to the funk of “Rock

You,” to the 21st century techno-blues of “Listen to

Your Radio Station.” Much of the album

will appeal to fans of Mark Knopfler and

J.J. Cale. On songs such as “Midnight

Creeper” and “Nice and Easy,”

Lee’s sweet-twang guitar sashays gently

to the shuffling grooves of bassist Pete

Pritchard and drummer Richard Newman. Still on the Road to Freedom also includes a vibrant remake of Ten Years

After’s “Love Like a Man,”

during which Lee plays several fluid guitar

solos that will leave listeners foaming at

the mouth.

In the sleeve notes, Lee accounts for the

record’s diversity by explaining that

he had 33 songs to choose from. “I

am never sure which direction my music is

going to take,” writes Lee, “but

I do know that to be worthwhile it has to

be a natural progression. It has to evolve

freely. For me it has to be instinctual and

not commercially premeditated.”

Rock Square contacted the guitarist via email to ask

him about Still on the Road to Freedom, his career with Ten Years After, and how

he’d love to change the world by bringing

back the values of 1969.

Still on the Road to Freedom is striking for its wide stylistic diversity—how did the record shape up that way?

As the 33 songs I had written developed and

evolved, I picked out the ones that showed

the most promise. As I continued to work

on them, I realized that they pretty much

went through most of my musical influences

and styles over the years.

So the time warp concept just appeared out

of the blue with no premeditated plan.

Still on the Road to Freedom is a very disciplined record in that it

clocks in at 42 minutes—almost vinyl length—rather than the sprawling length of 80 minutes

of so many CD albums. Given that

you had

33 songs written, was it difficult

to stick

to the discipline of releasing

a succinct

album rather than cramming as

many of those

33 songs onto a CD?

For me the CD has a beginning a middle and

two ends and works as an entity from start

to finish. I never even timed it until it

was finished, it just seemed the right length.

Guess I was born to make vinyls.

Elvis and early rock ‘n’ roll

was such a big inspiration for

you. Both

“I’m a Lucky Man”

and “Down

Line Rock” revisit that

sound—who were the guitarists who most influenced

you early on and which of today’s

players

do you most admire?

Big Bill Broonzy, Muddy Waters, John Lee

Hooker, Ralph Willis, Lonnie Johnson, Brownie

McGhee and the three Kings—B.B., Albert

and Freddy. Jazz wise, I listened to Django

Rheinhardt, Charlie Christian, Barney Kessel,

and Wes Montgomery and a bit of Segovia’s

classical and Juan Serrano’s Flamenco

on the side. I listened to the country playing

of Merle Travis and Shit Hotkins [Chet Atkins],

and for Rock and Roll it was Scotty Moore,

Chuck Berry and Franny Beecher.

These days I like to listen to J.J. Cale,

the king of laid back, and Mark Knopfler—he

has a unique style. Tommy Emmanuel, who has

obviously been practicing far too much and

there’s a new guy Jeff Aitchison, who

is doing amazing things on the acoustic guitar.

Stanley Jordan deserves a mention, he has

an amazing style which is more related to

keyboards than guitar and I also like George

Benson’s jazz work, but not the muzak

for swinging secretaries. Check out Billie’s

Bounce with Billy Cobham on drums and Herbie

Hancock on piano.

“Listen to Your Radio Station”

has a surprisingly contemporary

edge with

its drum loop sample by the late,

great King

Crimson drummer Ian Wallace—where did you find that loop and did the

song evolve out it?

This is a kind of cross between blues and

hip hop. Blues-hop or Hip Blues if you will.

The original recording was done to a click

track, and I later found Ian’s drum

rhythm which fitted perfectly. Myself, Ian

Wallace, Boz Burrell ,Tim Hinkley and Mel

Collins had a jamming band we called “The

Gits.” This was from one of the many

jams we did between ’71 & ’75

The album was recorded in Spain—is that why the improvised “Song of

the Red Rock Mountain”

has that Latin

classical guitar sound to it?

That tune is another one that just came out

of the blue. It has a Flamenco leaning as

I have been studying Flamenco guitar.

“Nice and Easy” has a laid-back, J.J.

Cale sort of shuffle to it was Cale an overt influence on the song?

Yes, I was definitely in Bradley’s

Barn mode when I recorded this.

What’s the lyrical message of “Back

in 69” about?

What happened to Peace & Love?

You’ve roped in the great keyboardist

Tim Hinkley on the album. What

makes him

your go-to guy for keyboards

since the early

1970s?

He is the best, he has the right feel for

me and he does not play too many notes. It’s

all about understanding the groove and he

understands and understates.

What inspired you to re-record “Love

Like a Man” for this album?

I liked the rhythm and the song fitted, just

jumped out of my head.

Are there other Ten Years After songs you

look back on and wish you could

re-record

them with today’s recording

techniques

and production?

I haven’t really thought about it but

it’s a definite maybe for the future.

“Working on the Road” springs

to mind. I’ve always liked the line,

“I’ve seen the world and it’s

seen me/ In a strange kind of way I guess

I’m free.”

In the liner notes, you wrote that you “decided

to take the road to freedom rather

than the

road to fame and fortune.” Have

you encountered any bumps in

your journey

down the road?

There are many bumps holes, forks and snakes

on the road to freedom but freedom is a relative

thing and it means different things to different

people depending on the circumstances. Think

of your own form of freedom and how to achieve

it, and you will find there are a lot of

sacrifices to make which are not easy. But

it’s worth it if you follow your instincts

and find the flow.

When you parted ways with Ten Years After

almost a decade ago, was that

because of

your journey down that road—and what’s your assessment of the band’s

legacy?

I actually parted with TYA in 1975. There

were a few reformation gigs which did not

add up to much. Any legacy that exists for

me, is on the recordings between 1967 and

the release of the Woodstock movie in 1970.

After that the spark was lost when it all

got too corporate and commercial.

To the best of my knowledge, Ten Years After

never performed its biggest hit,

“I’d

Love to Change the World,”

in concert.

Why was that?

It’s a great recording but it’s

no fun to play live, it’s too restricting.

Duplicating songs live has never been something

I wanted to do.

There are songs I like to listen to, songs

I enjoy creating and recording and songs

I like to play live. The live songs must

have room to expand and evolve….and

be fun.

Finally, do you reckon Spinal Tap ripped

off Ten Years After’s Stonedhenge?

No, I was never into the mysticism of the

henge, I just liked the “stoned”

part.